My Black History in Canadian Animation

I was watching the pilot episode of the new live-action drama The L.A. Complex. In one scene, a struggling (white) Canadian actress Raquel, tries to bluff her way into an L.A. audition for the “best friend part.” But the producer (also white) says she’s decided “to go another way…we’re going black.” Cut to a wide shot: the waiting room is full of black actresses. The producer says, “I really don’t want an all-white show. You know, it doesn’t really reflect reality.” Frustrated, Raquel inappropriately blurts out, “So you’re making the best friend black. It’s just kind of a cliché, don’t you think? I mean, who has a black best friend?…It’s a TV-only thing.”

It got me to wondering…is the “black friend” a cliché in Canadian animated series or does having a black character in a show’s cast “reflect reality?”

So in honour of Black History Month, I thought I’d touch on the touchy issue of ethnic diversity in Canadian cartoons, specifically black characters. I’ll use the term “black” even though it makes some of us Canadians uncomfortable. We usually use the politer-sounding “African-Canadian” or sometimes the more ethnographically-correct term “Caribbean-Canadian” (as most black Canadians are of Caribbean origin.)

YOU’VE GOT A FRIEND IN ME

Over the past decade, I’ve written for a few series where the black character is pretty much in the “friend-zone.” One was the title character’s best friend.

One was a member of a group of friends of the title character.

And one was a member of a team of heroes – but the leader was a white guy.

So in my experience, when you see a black character on a Canadian animation series, yes, he or she is usually either a friend of the lead or, more likely these days, part of an ensemble of characters.

Until a show creator manages to sell a production company and a broadcaster on a series featuring, say, the daring adventures of a black superhero from Halifax and his “white friend” sidekick, or the hilarious antics of Caribbean-Canadian family in Toronto, for now most black characters are “one of the gang.”

Some might see that as tokenism. But I see it as an attempt to reflect the multi-ethnic reality of North American society.

And I do say North American rather than Canadian society.

According to the 2006 census, the Canadian population was 2.5% African-Canadian, mostly living in urban areas of Ontario and Quebec. On the other hand, Asian and South Asians make up about 11% of the Canadian population. Yet you don’t see them represented as often in Canadian-made animation.

So what’s up with that?

The faces of North American reality shows are reflected in the cast of Total Drama World Tour (Fresh TV)

Well, consider that the US is an important market for Canadian animation. Their population is ten times ours with African-Americans making up about 12%. Having a US broadcaster aboard can make the difference between a series going into production, or dying at the development stage.

So from a sales standpoint, it’s good for business if your show reflects America’s ethnic diversity.

It’s interesting to note that in even in preschool animation – which often dodges the issue of ethnicity altogether and broadens their international marketability by having a cast of animals characters or brightly-coloured creatures – sometimes care is taken to give a non-human character a black vibe, for example Custard from The Save-Ums (voiced by African-Canadian actor Jordan Francis) or Tyrone and Uniqua in the US series The Backyardigans. Those producers feel it’s important for young children to have their “reality” reflected vocally.

MORE IS MORE

Of course, I’m not saying we have too many black characters in Canadian animation. What I’m hoping for is that in future, show creators will include even more characters of all ethnicities in their series. I’ve also written for Asian-Canadian and Latino-Canadian and First Nations characters in the past and it would be great to write for them more often. Canadian animation viewers from a non-European background ought to be able to see themselves represented onscreen, especially when TV programming is supported by Canadian tax dollars!

So to all the writers, show creators, production companies and broadcasters out there: Canada welcomes people of all cultures and ethnicities to make this country their home. Let’s help our animation industry reflect our reality.

Is Ruby's best friend Louise (left) a "bunny of colour" on Max and Ruby? (9 Story Entertainment/Nelvana)

You Asked For It: How many Locations should I use?

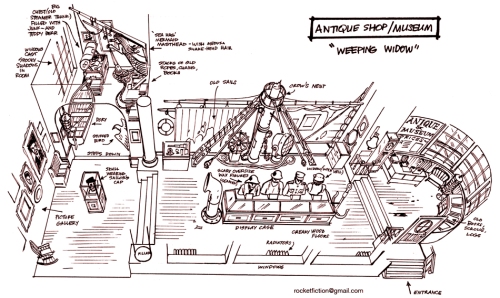

This dramatic exterior location from Nelvana's "Tales From the Cryptkeeper" is by artist Paul Rivoche. His amazing Rocketfiction artblog is full of astounding design work. Click the image.

This question about locations and Canimation’s response come from the comment section of our recent post, What Happened To Me Script? Part Three. It is a common enough query that we wanted to share it with our readers who don’t make a habit of checking out the comment section for each article.

Reader Josh asked: “I’m curious about your comment on locations – how limited are most animated series in terms of creating new backgrounds?”

Great question, Josh!

While animation can do more with backgrounds than many live action shows, they still have to be designed and rendered by the animation team. Remember, it’s not just a single design for each location, It’s backgrounds for EVERY shot that have to be planned and produced and rendered.

Another "Tales From The Cryptkeeper" by Paul Rivoche. Click the image to see more at his Rocketfiction artblog.

A good rule of thumb is that in the first half of season one, the production team is probably still developing all the main designs and sets that will will be used the most over the course of the series – the main characters’ homes, rooms, yards, school or headquarters, etc.

Once those locations that will be re-used every episode are established there is more time to expand the world. Even adventure shows that tend take our heroes all over the place will attempt to make use of established locations like a HQ or the interior of Ben 10′s motor home, etc. and try to use any new locations effectively.

I’d suggest avoiding more than 2 extra locations, 3 tops (and that’s pushing it on most shows). Also keep in mind a single location may serve your needs. An Inca Temple is technically one location, even if you’re using the exterior, interior tunnels and a treasure room deep inside.

And don’t be surprised if a new location gets changed. If you’ve written a short scene where the hero gets his orders at the Eiffel Tower but haven’t used the location for anything else in your story (a waste of a great locale!), the scene may be moved to an established, reuse location like the hero’s jet.

-RP

What Happened to my Script?! – Part Three

The length of this discussion concerning why an animation writer’s script gets changed after they’re done writing it has turned into a freaking trilogy, there was so much to say about it. I don’t usually write this much material without getting paid for it, so clearly I must feel impassioned and or enraged about the subject. It’s hard to tell sometimes.

In Part One, we discussed possible reasons why your script was changed between your last draft and the finished episode, with an emphasis on changes that could be due to stuff you did.

In Part Two, we discussed the various people who may have changed your scripts for reasons that were out of your control.

The final area of discussion, returns to the creative heads we mentioned earlier who handle your script after it’s finished. These are some specific types of changes that are made by these individuals, listed in chronological order of production stage:

● Script Length

Your script is too long, even after the Story Editor does their final pass on it. This problem is usually caught right away, and other times not until after the voice record, when all the actors’ takes are cut together in their proper pacing and the end result makes the episode many minutes too long.

Unless the series is called The Sopranos, the episodes must always be the same length – without exception. Which means stuff has to get cut. Jokes are usually the first casualty, because cutting them doesn’t affect story comprehension as severely.

Often times, if a line is rewritten at this stage, it’s usually to help with a story hole that was created because of other material that was excised.

● Actor’s reads

"Oh yeah! We're tossing out the script and ad libbing, baby! Let's make this sucker our own!" (Image from Phineas and Ferb)

Professional voice actors are a joy to behold when they read your script. The best ones make your dialogue sing. But it isn’t until all the lines are cut together sequentially that the creative heads discover where the episode’s weaknesses lie:

In the story itself.

In the pacing.

In deliveries that sounded great during the record that now sound too manic, too subdued, too over-enunciated, too everything.

These lines must either get re-recorded, or rewritten to help them play better in the finished episode.

● Storyboards

Your lovely description of a Yak valiantly climbing up Mount Everest over a long, arduous week proves to be incredibly boring when it’s storyboarded.

So a new scene showing a TMZ-type reporter doing a story on how the Yak– who already climbed to the peak months ago — is now the most celebrated Yak in all of Yak-dom and just wants to be left alone, is written by the Director to make the show faster and peppier.

● Animation

Animation is a team sport, with the script passed around after it leaves your desktop. It's how you play without the puck that makes the difference. (Image from Chilly Beach)

The quality of the animation being done is a big determining factor in what cuts and changes occur, post-writing. If a character’s walk cycle always looks silly when they try it, any scene you wrote showing that character walking will be changed to that character driving a car, taking public transit, or being hauled about in a rickshaw.

● Editing

Once all the editor splices together the various changes to your script, your episode becomes the sum of many parts. (Image from Spliced)

The culmination of all the above instances reaches its endgame here. Do we really need that one line from a minor character whose five other lines we cut earlier, or can now eliminate his part entirely? One action sequence is animated so well, the editor reuses it multiple times, adding extra length which must now be cut from another part of the episode. A decision is made to add a recap from a previous episode, or a new V.O. is added, leaving even less time for your stellar writing.

● Sound Mix

"Uh, Mister Sound Editor? Can we get a level on my diabolical, alien kat here before he shatters my eardrums?" (Image from Kid vs. Kat)

A heart-swelling music sting or kickass explosion sound effect is emphasized over some less-than-pivotal dialogue, which was O.S. anyway, so nobody but you ever knew it was dropped in the first place.

By this point, if the cumulative rewriting done on your script is bad enough, you’ll wish they put music and explosions over the entire episode.

Looks like we’ve finally reached the end… of my patience for listing reasons why your animated script gets changed after you’re done writing it.

Not the list itself.

Because just like George Carlin’s famous routine “Seven Things You Can’t Say On TV” grew from its initial seven words to a list that takes seven minutes just to say them all, the plethora of reasons why a cartoon script gets changed will inevitably be expanded in the future.

– DeeAzz

2011 Gemini Awards – Animation Winners

Canimation belatedly celebrates this year’s Gemini Award winning animation writers and shows!

“A big congratulations to all of tonight’s Gemini Award winners,” says Helga Stephenson, Interim CEO, ACCT. “We are delighted to be celebrating with such sensational Canadian talent who are truly outstanding representatives in their fields.”

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves. So let’s take a moment to celebrate all the nominees as well as the winners.

Best Animated Program or Series

(Sponsored by the Canada Media Fund)

Nominees

Glenn Martin DDS

City TV (Rogers) (Cuppa Coffee Studios)

Adam Shaheen

Jimmy Two Shoes

Teletoon (Astral/Corus) (Breakthrough Entertainment)

Ira Levy, Mark Evestaff, Peter Williamson

Kid vs. Kat

YTV (Corus) (DHX Media Ltd.)

Blair Peters, Chris Bartleman, Chantal Hennessey

March of the Dinosaurs

Shaw Media (Shaw Media)

(Yap Films, Wide Eyed Entertainment)

Elliott Halpern, Pauline Duffy, Jasper James

And the winner is:

Hot Wheels – Battle Force Five

Teletoon (Astral/Corus) (Nelvana Limited)

Doug Murphy, Tina Chow, Ken Faier, Ace Fipke, Chuck Johnson, Pam Lehn, Audu Paden, Ira Singerman, Barry Waldo, Irene Weibel

Best Direction in an Animated Program or Series

Nominees

Kid vs. Kat – Kat To The Future Part 1

YTV (Corus)

Rob Boutilier, Josh Mepham

League of Super Evil – Voltina

YTV (Corus)

Sebastian Brodin, Steve Sacks

Hot Wheels – Battle Force Five – Sol Survivor

Teletoon (Astral/Corus)

Johnny Darrell, Mike Dowding, Andrew Duncan

Rob the Robot – Puzzled

TVO (TVOntario)

Phillip Stamp

March of the Dinosaurs

Shaw Media (Shaw Media)

Matthew Thompson

And the winner is:

Glenn Martin DDS – Date with Destiny

City TV (Rogers)

Ken Cunningham

Best Original Music Score for an Animated Program or Series

Nominees

Kid vs. Kat – Fangs For The Memories

YTV (Corus)

Hal Beckett

Sidekick – Identity Crisis/Fart of Darkness

YTV (Corus)

Don Breithaupt, Anthony Vanderburgh

Rob the Robot – Space Race

TVO (TVOntario)

Serge Côté

And the winner is:

League of Super Evil – Ant-archy

YTV (Corus)

Hal Beckett

Best Performance in an Animated Program or Series

Nominees

Jimmy Two Shoes – Bird Brained

Teletoon (Astral/Corus)

Sean Cullen

Stella and Sam – Night Fairies

Playhouse Disney Canada (Astral)

Rachel Marcus

Stella and Sam – Night Fairies

Playhouse Disney Canada (Astral)

Miles Johnson

League of Super Evil – Force Fighters VI

YTV (Corus)

Colin Murdock

And the winner is:

Babar and the Adventures of Badou – Neigbourly Nice Day 19A

YTV (Corus)

Gordon Pinsent

Best Pre-School Program or Series

Nominees

Dino Dan

TVO (TVOntario) (Sinking Ship Entertainment)

J.J. Johnson, Matthew J.R. Bishop, Blair Powers

Kids’ Canada – Wowie Woah Woah

CBC (CBC)

Phil McCordic, Sid Bobb, Erin Curtin, Ali Eisner,Nadine Henry, Marie McCann, Patty Sullivan

Stella and Sam

Playhouse Disney Canada (Astral)

(Radical Sheep Productions)

John Leitch, Michelle Melanson

TVOKids – Gisèle’s Big Backyard

TVO (TVOntario)

(TVOntario)

Jennifer McAuley, Gisèle Corinthios, Patricia Ellingson, Paul Gardner

And the winner is:

The Mighty Jungle

CBC (CBC)

(DHX Media Ltd.)

Katrina Walsh, Charles Bishop, Michael Donovan, Beth Stevenson

Best Writing in a Children’s or Youth Program or Series – Sponsored by the Independent Production Fund

Nominees

Almost Naked Animals – Better Safe and Sorry

YTV (Corus)

Seán Cullen

Degrassi – My Body is a Cage Part 2

MuchMusic (Bell Media)

Michael Grassi

League of Super Evil – Voltina

YTV (Corus)

Philippe Ivanusic-Vallee, Davila LeBlanc

How to be Indie – How to get Plugged In

YTV (Corus)

Anita Kapila

And the winners are:

Spliced – Pink

Teletoon (Astral/Corus)

Richard Elliott, Simon Racioppa

Best Cross-Platform Project – Children’s and Youth – Sponsored by the Bell Broadcast and New Media Fund

Nominees

Skatoony Interactive

Teletoon (Astral/Corus) (marblemedia)

Mark J. W. Bishop, Ted Brunt, Julie Dutrisac, Matthew Hornburg, Johnny Kalangis

Stella and Sam Interactive Adventures

Disney Junior (Astral) (Zinc Roe Inc.)

Anne-Sophie Brieger, Robert Ardiel, Jason Krogh, Davin Risk

The Baxter Online Experience

Family Channel (Astral)

(Shaftesbury / Smokebomb Entertainment)

Shane Kinnear, Jay Bennett, Daniel Dales, Nicole Mickelow, Jarrett Sherman

And the winner is:

Babar and the Adventures of Badou Interactive

YTV.com (Corus) (Watch More TV Interactive Inc.)

Caitlin O’Donovan

The Call me Fitz pilot took top honors for Best Sound in a Comedy, Variety or Performing Arts Program or Series. But two animated entries also earned nominations in this category.

Bolts & Blip – Robots Don’t Dream Part 1

Teletoon (Astral/Corus)

Roberto Capretta, Kevin Bonnici, Melissa Glidden, Edwin Janzen, Tim O’Connell

League of Super Evil – Ant-archy

YTV (Corus)

Jonny Ludgate, Ewan Deane, Steffan Andrews, Pat Haskill, Gordon Sproule

And finally, an animated property won for Best Cross-Platform Project – Fiction.

DatingGuy.com

Matthew Hornburg, Mark J. W. Bishop, Ted Brunt, Julie Dutrisac, Johnny Kalangis

Congratulations one and all. Better late than never, right?

David Dias Twitter chat transcript August 14, 2011

As if his recent appearance on TV Writer Podcast (linked in the post below) weren’t enough to inspire and inform, here’s a link to the transcript of his August 14 twitter chat session!

http://www.tvwriterchat.com/2011/08/transcript-from-aug-14-2011-chat.html

David Dias interview on TV Writer Podcast

Need some inspirational and helpful hints on working in the animation industry? Check out this fun and informative podcast.

Canadian animation writer/creative producer/story editor David Dias speaks with TV Writer Podcast host Gray Jones in a one–hour interview jammed-packed with tasty tidbits. “All the ins and outs of writing animation for all ages, including many great tips on breaking in, pitching, and getting your idea off the ground. ”

Sponging Off the System: Are Animation Writers Merchants of Stupidity?

Once again, animated television – the beloved medium which puts roofs over our heads, coffee in our cups, and digital cable programming into our PVRs – has come under attack.

Some researchers from the University of Virginia showed 20 4-year-old kids an episode of Spongebob Squarepants then had them do some tests to measure their “executive function.”

Executive function. Sounds like a cocktail party for a bunch of CEOs, but apparently it’s something happens in your frontal lobes. It comes in handy when you want to learn stuff, keep organized, control your impulses and learn from your mistakes. (If my lobes had better executive function, I probably would not have gone to see Green Lantern this summer.)

Anyway, the Spongbob kids reportedly performed more poorly than the 20 kids who watched an episode of Caillou or the 20 kids who drew pictures instead. This led to the researchers to conclude that fast-cutting quick-paced shows like Spongebob could impede the learning process.

Okay, lots of folks, including a spokesdude from Nickelodeon, have already pointed out the flaws in this study…including the small sample size and the fact that Caillou is a preschool show and Spongebob is aimed at older kids. Or that the study didn’t try leaving a gap between the watching of the programs and taking of the tests.

But what if the results aren’t bogus? What if a study with a larger sample of kids comes up with the same results? What if we, the animation writers, are contributing to the stupidity of children?

The solution to this particular problem seems pretty simple to me. PARENTS OF PRESCHOOLERS: DON’T LET YOUR KIDS WATCH SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS BEFORE THEY TAKE AN EXECUTIVE FUNCTION TEST!

Let’s say some kids shouldn’t watch TV before trying to learn something. (And let’s say I shouldn’t have watched two of episodes of Kick Buttowski on YouTube before writing this post. Think of how more coherent it could’ve been!)

Then let’s say parents should control what shows their kids watch and when they watch them and for how long. After all, raising and educating their children is their job.

Our job is to provide a product. Some might say a seductive, addictive product…

ARE WE BIG ANIMATION?

TV has often been blamed for producing a generation of obese, socially-misfit couch potatoes with attention deficit disorder and an inability to relate to real people…but enough about animation writers.

This is about the children and the money we make writing for them.

Is animation the Big Tobacco of television programming? The more eyes on screens and the more brand loyalty generated for spin-off merchandise, the higher the profits for networks and production companies. Which leads to more work for us, the animation writers and story editors.

By making our scripts as entertaining as we possibly can, are we part of a system designed to hook viewers at an early age, leading to a lifelong dependence on the medium? After all, they do call it viewing habits.

Well, whether the general public realizes it or not, writers, story editors, producers and network execs all work towards keeping their kids’ shows age-appropriate, with positive messages about friendship and cooperation, self-confidence and persistence, consequences for one’s actions and all that good stuff. And animation has had a long association with educational programming, teaching kids about the world around them and helping them with literacy and numeracy and problem-solving skills.

Lots of things in life are bad for you if consumed in large amounts…booze, Facebook, Chocolate Cheerios…and TV is no different. It’s up to parents, caregivers and teachers to help kids learn to moderate their consumption of, well, everything.

But I’m willing to do my part. So hey kids, turn off that TV and go run around outside for a while. Just not when my episode is on.

What Happened to My Script?! – Part Two

Canimation's got a bucketful of creators and executives who weigh on your script after it goes in. (Image from Harry and his Bucketful of Dinosaurs)

In What Happened To My Script? – Part One, we discussed the reasons why your script was changed between your last draft and the finished episode, with an emphasis on why those changes were because of stuff that you did.

Not anyone else — You.

Now comes the fun part where we turn the tables and examine the reasons why your script was changed that have to do with some other animal, vegetable, or mineral.

Meaning it’s someone else’s fault. They’re the one who ‘messed it up’… or made it awards-worthy, although you would never admit that.

"We've searched the entire universe for someone to blame. I say it's that binary star's fault!" (Image from Flying Rhino Jr. High)

The reasons why a script changes after the original writer has moved on has everything to do what goes on behind the animated curtain. Specifically, the later production stages. Many animation writers have no idea what goes on after they hit ‘send’. But they should, because it would help them become better writers and deliver more consistently ‘animate-able’ scripts. But until productions begin putting a “Welcome Writers!” sign up on the door for these later stages, how else are you going to learn why your sh%$ got changed?

(For more info on the Production Process, check out You Are Never Writing Alone -learning the animation process and The Animation Production Process, Part 2 – The Visual Stream – Editor)

Like their counterpart productions in the live-action world, animation productions are big collaborative efforts. Like a Final Draft baton being passed from hand to hand, your script travels through many different departments before it reaches the TV screen, and the reasons for changing your words range from the logical and budgetary, to the arbitrary and ego-driven.

The number of people who poke, prod, fondle, slap, or even stab your script to death is a long one. So perhaps it’s best to just list those individuals first, then explain the reasons why they changed your script.

The reasons they changed my script because of THEM:

● The Head Writer

"Bwahahaha! Now I, the Story Editor/Head Writer/Executive Producer, shall have the final laugh with my infamous 'sparkle pass'!"

Whether they go by that designation, or by Executive Producer, or Story Editor (the most common), the Head Writer of the animated series you’re writing for will often edit your script at every draft stage. This is preferable to the alternative where they only edit it after you’re done your Polish, for the main reason that you as the episode’s writer, get a unique glimpse into their creative mind by reading their revisions along the way. Reading their edited passes (always recommended) allows you to see what they like or don’t like about your writing, and helps you learn to write better for them.

NOTE: This is a very different thing than helping you learn to become a better writer. You will not always agree with the liberties the Head Writer took with your script. Many times you’ll think what they did suck ass. But in the greater employer/employee universe, never forget that you’re the subordinate being hired to give them what they want. Save your artistic expression for your own projects, and give them what they want already.

The alternative to a Story Editor editing your script at every stage, is when they just relay notes from the broadcaster, or whoever has a say in the script, directly to you, the writer, to implement. Only when you’re done your last draft in this scenario does the Story Editor do any rewriting themselves. From a notes perspective, all the bigger problems should have been ironed out by this stage, so anything from this point on is most likely the Story Editor getting their own creative rocks off, or juggling last-minute notes to get the damn thing out of their hands forever. Their draft can be anything from a light polish to a complete rewrite depending on their creative temperament.

● The Animation Director

"Seriously dudes and dudettes. You've gotta see this show through an animator's eyes. Try mine." (Image from Beetlejuice)

This creative head always has their own vision for the series, and for your script. It’s what they’re paid to have. So in terms of what we will see on screen, the artistic buck stops at them. And in that capacity, the Director will put their stamp on your episode in whatever way they see fit. This stamp could include rewriting the odd line of dialogue, entire scenes, or in rare cases, the entire script.

Good Directors will only do what they need to enhance your script because the bigger story demands should have already been addressed by the Story Editor. This leaves the Director to focus solely on making the show look great and play out well dramatically. Not-so-good Directors believe that any script that wasn’t written by themselves sucks and will change every word that either you or the Story Editor wrote. Because they can.

Like it or not, your script will always be filtered through a Director’s sensibility. When your vision jives with theirs, the end result is magic, and the show becomes bigger than the sum of its parts. When your vision doesn’t merge with the Director’s, it’s usually a disaster in the making. Not to mention a heartbreaking experience for the writer who spent endless hours crafting a script that got moulded into some other beast for broadcast.

● The Producer

"Hey guys. Is there room for a little product placement for this way-cool, zoomy car? It'll help pay for all the bloody actors your script is using." (Image from Gerald McBoing-Boing)

Somebody has to keep the budget and schedule of an animated production in line. If your script is a negative influence on either of those aspects, rest assured that the Producer will tag it with a bullseye. You included a new location in your script? The Producer has to pay an artist to draw it. You introduced a new character who only says two lines? The Producer has to pay an actor to read those two lines (FYI – you’d do well to research how ACTRA voice actors get paid. Word count matters. In some cases, losing one word from one line can save the production hundreds of dollars).

Unlike Directors and Story Editors, Producers aren’t always creative. Nor do they have to be. Some are only paid to handle cheques and calendars. In the live-action series world (specifically the U.S.), they’d be called ‘Non-Writing Producers,’ who deal only with logistics. This species of Producer generally leaves writers alone as long as they don’t mess with their budget or schedule.

Other Producers however, integrate themselves into the creative process in ways which overlap with all the other creative heads: the Writer, Story Editor, and Director. They give notes on your script. Attend voice records. Make cuts in edit sessions. In the animation world, there is no hard and fast rule for what a Producer does or doesn’t do within the creative spectrum. It’s different with every Producer on every series. And much like the Writer’s relationship with the Director, if the Producer is in sync with you creatively, the show will work fine. If not, expect to feel pain in all your creative places.

Additionally, it’s important to note that the Producer is the individual who represents the commercial and creative interests of the Production Company making the series you’re writing on. Your relationship working with this Producer could determine whether or not you’ll have a long, fruitful relationship with that production company, or never work for them again. Either of which could be a blessing or a curse.

● The Network Executive

"We must find a way to put my stamp on this perfect script, Minimus. Or I swear, someone's gonna get atomized." (Image from Atomic Betty)

This person wields a huge amount of power over your script. A single, dismissive comment from them could kill your episode at any stage. But like everyone else involved in the production, they want it to be as good as it can be. Their notes on your script can run the gamut from being constructive to infuriating.

When it comes to your script, the other creative heads on the production generally handle anything that’s too serious coming from the Network Executive. So when you receive the Executive’s notes, they’ve usually been edited down to the more manageable stuff. The more experienced you get, you’ll more likely you’ll get to receive all their notes (whoopee!). Be aware that the more you get to know Network Executives on a personal level, and the more they get to know you, the more receptive they will be to your writing… and to forgiving any choices you make that they don’t like. Meaning they’ll just ask for changes in the next draft… and not necessarily demand that you get fired immediately.

So those are the main culprits who are responsible for changing your script after you’re done writing it. But there are also some specific reasons that are worth mentioning as well. Specifics that will outlined in a rousing Part Three cliffhanger to this blog entry.

Stay tuned for What Happened To My Script – Part Three!

– DeeAzz